From the Soil to Living Law

In 1902, French archaeologists at the city of Susa in modern-day Iran unearthed three heavy rock fragments. When reassembled, the fragments formed a 2-metre-high stone slab called a ‘stele’. This is the Hammurabi Code. It is the most comprehensive legal compendium in all of antiquity. Carved upon its face is a mosaic of intricate pictographic symbols. When deciphered, the symbols describe 282 laws and dictates that governed daily life in the Cradle of Civilisation circa 1750 BC. Among them are the first insurance policies ever written. These extend from maritime insurance coverage to flood, trade credit, and even ransom policies. Individuals, religious temples, communities, and courts paid the claims.

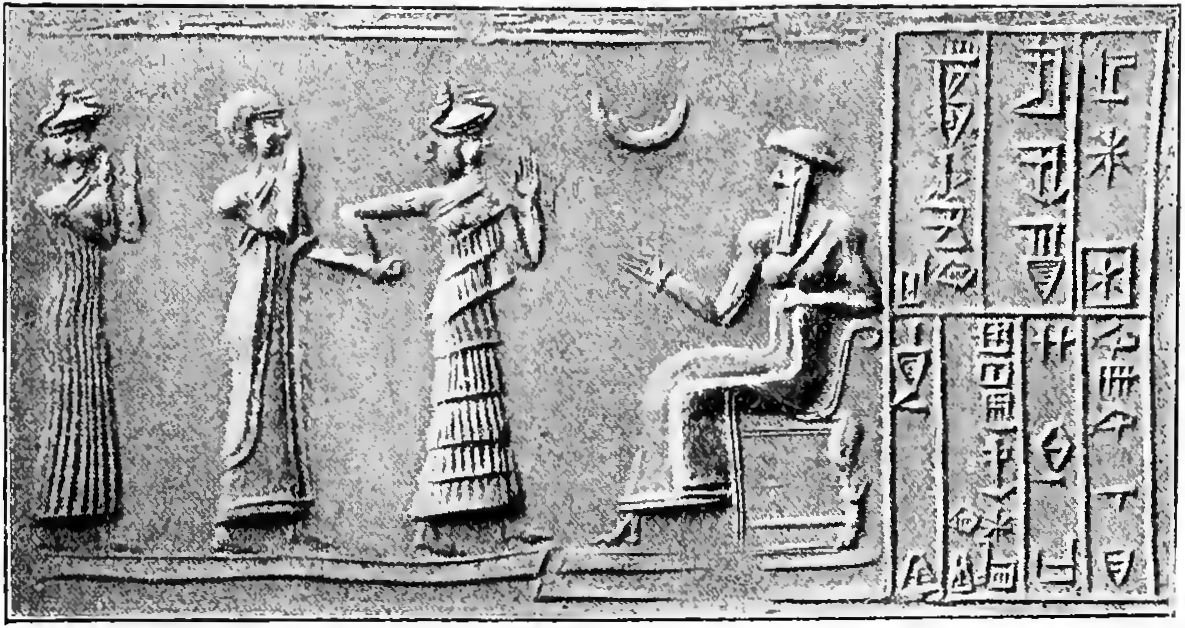

The Hammurabi Code today: the cuneiform symbols at left, the assembled stele at right.

The statutes were used for thousands of years and in places scattered far from Ancient Babylon. The ‘golden thread of criminal law’, the prosecution’s duty to prove the guilt of an arrested person and that person’s presumption of innocence, was iterated in English criminal law in 1935. The same notion was carved into the Hammurabi Code 3700 years before. The Roman phrase Res publica is translated to English as ‘Commonwealth’. Res publica was a legal system securing certain rights for all Romans. But the Romans, revered by Enlightenment thinkers and instrumental in inspiring the American Revolution and the creation of the United States, didn’t codify their laws until 2278 years after the Ancient Babylonians. Scholars today glorify classical antiquity just as Enlightenment scholars did. Greece and Rome were and are considered the birthplace of reason and progress. These beliefs have held since the 17th century. Edgar Allen Poe wrote of “the glory that was Greece” and “the grandeur that was Rome”.

Beyond Greece and Rome: The Cradle of Commerce

The same level of admiration didn’t extend to the Mesopotamian civilisations whose jurisdictional advancements led to the antecedents of modern nations: the city-states. But the ancient world precisely formulated its laws. This enabled a widespread system of trade and advanced commercial methods. Their eclipse is regrettable because just as the ‘golden thread’ is essential to modern criminal law, the financial arrangements of the Ancient Mesopotamians still have utility.

From the Bronze Age banks of the Tigris and the Euphrates and to the shores of the Mediterranean, lawmakers, merchants, farmers, priests, courtiers and traders used the Hammurabi Code, extended it, adopted older practices, and so created a place where risk was controlled in a versatile, pragmatic way. It was in Babylonian temples that the world’s first banks were created. The same temples and the people who met there, helped form the first insurance policies. The earliest policy guaranteed that a person who paid a ransom for a Babylonian citizen kidnapped during a war would be reimbursed.

Ancient Babylon’s geographic reach in green, superimposed over modern nations.

The Hammurabi Code: a Sophisticated Financial Blueprint

Hammurabi himself, the king who commissioned the Code, was keenly interested in finance and law. If used today, his methods could limit financial inequality, stabilise economies and reduce the possibility of loss, or injuries to individuals and businesses.

The Code strictly regulated interest rates, preventing predatory lending and ensuring debtors had a reasonable time and chance to repay. Excessively high interest rates in modern economies can lead to crushing debt burdens. Payday lenders and similar schemes lead to the same. If soundly adapted, Hammurabi’s interest rate caps could limit such inequalities.

The Code also greatly relieved debtors affected by natural disasters, crop failures, or other uncontrollable events. This was important in agrarian Ancient Babylon. Creditors too were protected, and allowed to receive different forms of repayment, equal in value to the debt. The Code governed various similar agreements between all Babylonian citizens. Modern economic systems could benefit from comparable policies, especially during crises like pandemics, natural disasters, or economic downturns.

The Head of Hammurabi, an obelisk from 1790 BC.

Ancient Mesopotamians were the first people to formalise hedging. Merchants, who shipped goods like grain and textiles in multiple vessels, etched risk-sharing contracts into tablets, and used insurance to mitigate losses. Occupying the Fertile Crescent (much of the modern-day Middle East), the Mesopotamians traded along the Tigris-Euphrates river system and, later, throughout the Mediterranean. Ships, boats and ferries ran constantly along watercourses, bringing food and currency (the two sometimes often substituting for each other), ornaments, clothes and other luxury items back and forth across an area which would, later, become part of the world’s largest trading network, the Maritime Silk Road. Mariners exchanged tangible items and intellectual and cultural advancements. The Mesopotamians expanded mercantilism, and developed financial instruments to protect their products, from receipts to charterparty agreements and bills of exchange.

The Modern Illusion of Control

Modernity, with its reliance on predictive analytics and punditry, too often teaches overconfidence. It sells the illusion that dangers can be anticipated, so all risks are manageable. There is an assumption that with more data, better algorithms and statistical models with increasingly jargonistic names, it is possible to master risk. But financial calamities, pandemics, terrorist attacks, insolvencies, and other impactful events elude forecasts and forecasters. Black Swan events, rare incidents with extreme impacts occur. Psychological biases cause people to create explanations for these events, as if they could have been predicted, and so may be predicted later should they happen again.

A schematic of the illusion of control and its consequences.

Mesopotamians had a more realistic view of uncertainty and inherent risks. They knew that not all risks could be predicted or controlled, so they built legal mechanisms that acknowledged the possibility of failure and natural disasters. Their laws aimed to buffer individuals and society against disaster, rather than to try and predict and avoid it. They accepted that unforeseeable events were part of life.

Divine Guidance, Elegant Risk Management

Religion, oaths and gods were central to the lives of the Ancient Mesopotamians, which is why the first banks arose in temples. People look to models as diviners of a different sort for answers today. The Ancient Babylonians used divine prophecies as guides and not guarantees. That is part of why the Hammurabi Code exists and why oaths are important to many of its laws. When viewed through modern eyes, some of the punishments in the Code can seem brutal. The Babylonians took slaves and sold them, and sentences in the Code certainly delivered people into that miserable existence. But any discerning person can look past those and see what is, fundamentally, an elegant set of rules. Some sections are pitiless, but most are remarkably fair. Their simplicity doesn’t reflect a simple society. Ancient Babylon was, at its peak, an immense economic and military power, with bustling cities extending to remote farmlands. It was a place of many different languages and peoples.

Ancient Mesopotamians perform acts of worship in a temple.

Lessons from the Ancients: Understand Uncertainty, Ignore Premonition

The Ancient Mesopotamians were humble. They acknowledged the unknown and accepted it. That humility is instructive. Instead of striving for complete prediction, embrace uncertainty and prepare for the unexpected. It is possible to mitigate risk, but not through premonition, whether your own or anyone else’s. Nobody knows what will happen in the next second, minute, hour, day, month, or year. Insure commercial transactions. Use credit checks, assess potential customers or find those who can do that. Adjust payment terms where necessary. Be aware of alternate suppliers. Stress-test your business using multiple scenarios, and do so regularly. Consult trade credit brokers.

Nobody would be harmed by reading the Hammurabi Code or any of the laws of the same period. On the contrary, it’d be a brief and helpful activity. Because by embracing the wisdom of the ancients, modern businesses can flourish in an uncertain world.